Why are some companies able to create ‘blue oceans’ of uncontested market space while others struggle in ‘red oceans’ of intense competition?

To answer this question, we need to look at some examples from a range of industries and identify the specific strategic actions blue ocean companies took to achieve profitable growth.

We’ll examine blue ocean strategy examples from the tech, healthcare, fintech, and retail industries and a classic blue ocean example from the entertainment industry.

We’ll also take an in-depth look at how one company made the spectacular transformation from the red ocean to the blue ocean.

History reveals that there are no perpetually excellent companies. The same company can be brilliant at one moment and wrongheaded at another. It would appear, therefore, that the company per se is not the appropriate unit of analysis when exploring the roots of high performance.

In their bestselling book, Blue Ocean Strategy, Professors Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne write:

The strategic move, and not the company or the industry, is the right unit of analysis for explaining the creation of blue oceans and sustained high performance.

A strategic move is the set of managerial actions and decisions involved in making a major market-creating business offering.

The following blue ocean strategy examples all highlight strategic moves that delivered products and services in a way that opened and captured new market space, with a significant leap in demand.

1. Marvel – a super-powerful blue ocean strategy example

2. Nintendo’s switch to a blue ocean

3. Stitch Fix – a blue ocean example in the fashion retail industry

4. HealthMedia – a blue ocean strategy example in healthcare

5. Nickel – a blue ocean in the fintech industry

6. Yellow Tail – a blue ocean example in the wine industry

7. Cirque du Soleil – a classic example of blue ocean strategy

Let’s jump right in, starting with one of the most extraordinary blue ocean turnarounds in corporate history.

Marvel – a super-powerful example of moving from a red ocean to the blue ocean

Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the last 50 years, you have certainly heard of Marvel, or at least, you’ll be familiar with Marvel characters such as Spiderman, The Hulk, and many others. What you may not know is that Marvel is an example of one of the great red ocean to blue ocean transformations in modern business history.

Consider the big movies of the last decade. Year after year, Marvel movies have smashed their way to the top of the earnings charts. The Avengers, Age of Ultron, Infinity War, Endgame, and Black Panther are the five highest-grossing superhero films of all time, accounting for half of the lifetime top-ten grossing films of any genre. In fact, Endgame is the highest-grossing movie ever. All were produced by Marvel.

Things were not always so bright for Marvel, however. Just over two decades ago, the firm emerged from bankruptcy saddled with USD $250 million of high-interest debt, a decimated sales channel, disgruntled customers, and a skeleton staff of employees. Cash flow was so tight they struggled to make payroll.

The early years of Marvel

Founded in 1939 as a comic book company, Marvel plodded along in its first few years at a time when superheroes had fallen out of fashion. Their only well-known character was Captain America, invented specifically to encourage Americans to support WWII. By the 1960s, Marvel’s unoriginal, ‘me-too’ comic book division was almost closed down. It was at this point that three middle-aged men – Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and Steve Ditko – decided to build a new type of superhero, one that was human first and superhero second.

Rather than aim for the existing comic buyers, who were children, Marvel created new, more complex characters that appealed to college students – noncustomers of the comic book industry up to this point. From 1960 to 1964, the company introduced Spider-Man, Iron Man, The Hulk, The X-Men, and many other characters – about 8,000 in all. Marvel saw its comics business thrive.

All this was to change in the 1980s when Marvel’s new owners took a red ocean approach that sucked all the value out of the brand. During this time, management pocketed hundreds of millions of dollars while decimating Marvel’s staff and retail channels, leaving customers alienated and confused. Eventually, the business went bankrupt.

Marvel took a blue ocean turn by focusing on noncustomer college students. Marvel invented characters that were people first and superheroes second: Spider-Man, The Hulk, Iron Man, the X-Men.

Marvel’s blue ocean strategic move

In 1999, Peter Cuneo, a world-renowned turnaround expert, was appointed CEO of Marvel. He is credited with taking Marvel from bankruptcy to being acquired by Disney for over $4 billion in just over a decade.

Cuneo and Marvel’s most vital blue ocean strategic move was entering the motion picture industry, a blue ocean strategic pivot that saw the company roar back to success in the 21st century in the form of Marvel Studios.

Not only that but Marvel and Cuneo transformed the whole movie production model; that is, it fundamentally changed how a movie is made. Marvel’s strategic move saw it not only enter a new field but reconstruct that field to open a blue ocean.

How Marvel broke the value-cost trade-off

Many in the business world hold to the conventional belief that companies can either create greater value to customers at a higher cost or create reasonable value at a lower cost. Viewed this way, strategy is seen as making a choice between differentiation and low cost, a value-cost trade-off. It’s the mindset of a red ocean strategist.

Marvel, on the other hand, took a blue ocean approach, pursuing differentiation and low cost simultaneously. To get a better understanding of how this works, let’s review Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne’s Four Actions Framework.

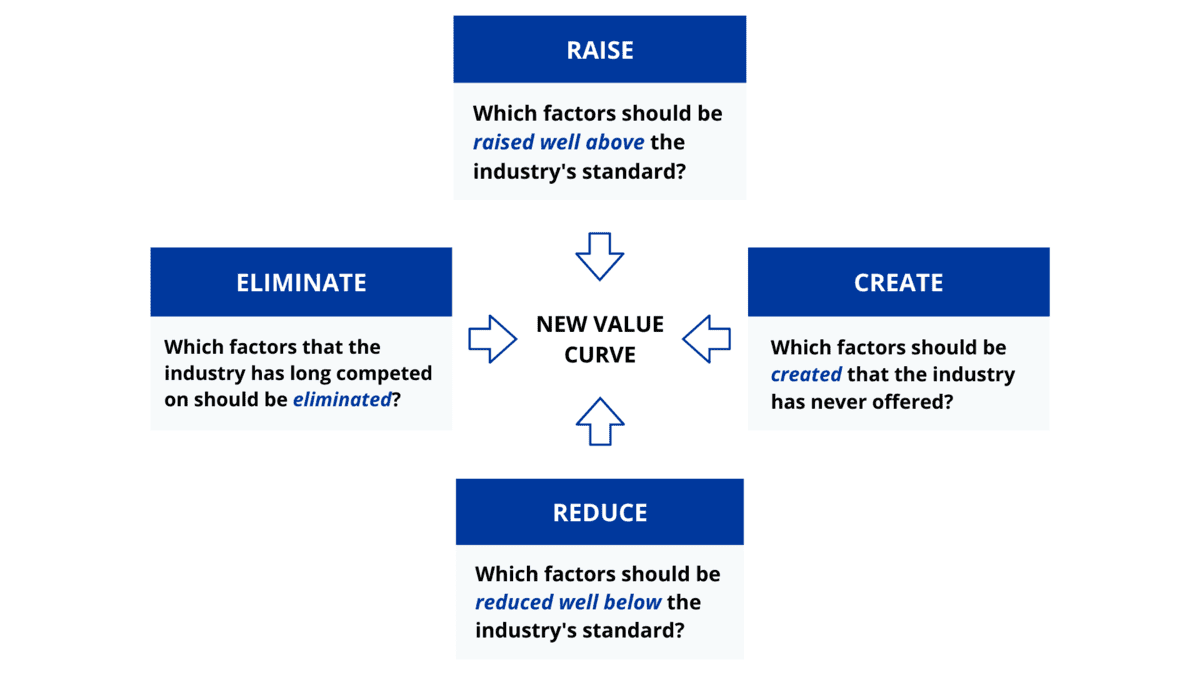

To break the trade-off between differentiation and low cost, the framework poses four key questions to challenge an industry’s strategic logic:

- Which factors that the industry takes for granted should be eliminated?

- Which factors should be reduced well below the industry’s standard?

- Which factors should be raised well above the industry’s standard?

- Which factors that the industry has never offered should be created?

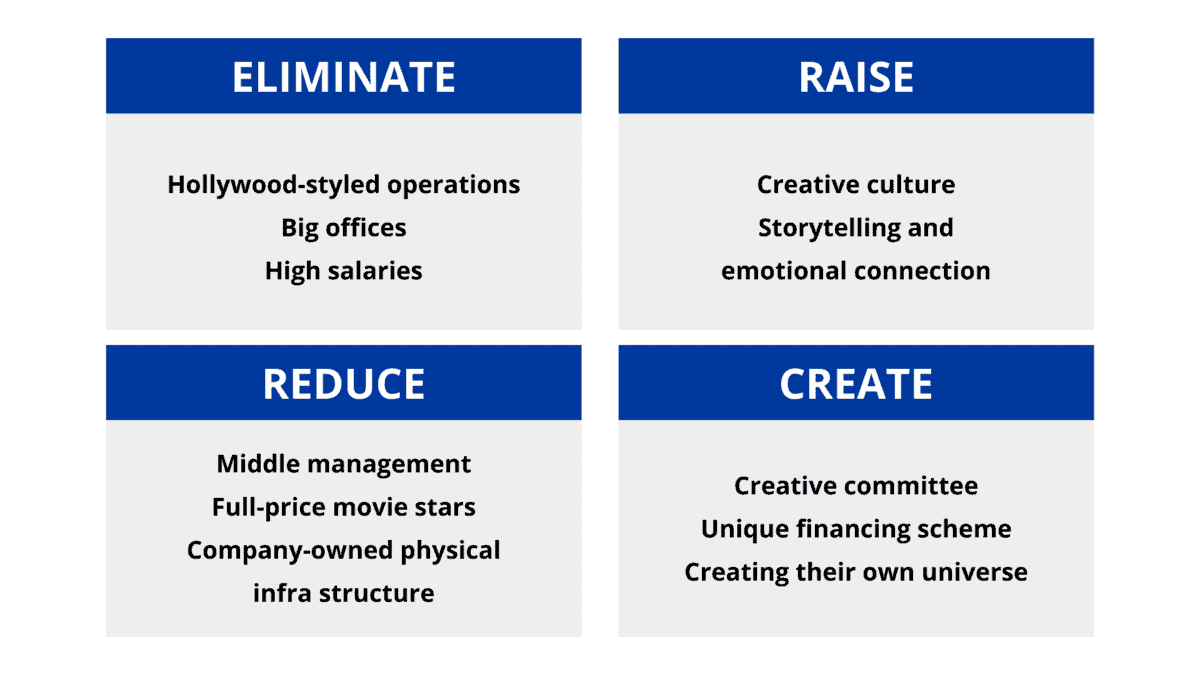

Marvel’s ERRC Grid

© Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne. Blue Ocean Strategy. Blue Ocean Shift. All rights reserved.

The Eliminate-Reduce-Raise-Create (ERRC) Grid above shows how Marvel was able to break the value-cost trade-off, i.e., strategic actions that created unprecedented value at low cost.

The Marvel blue ocean example illustrates how a company used differentiation and low cost to restore its blue ocean business. By entering the motion picture industry and value innovating the motion picture production model, Marvel restored its blue ocean to become the most profitable movie franchise in history.

To learn more about how Marvel created a blue ocean, check out The Marvel Way: Restoring a Blue Ocean, a case that has won the 2020 Case Centre Award for Strategy and General Management.

Nintendo’s switch to a blue ocean

Nintendo, the Japanese video game company created its first console in 1977 and became internationally famous with the release of games Donkey Kong in 1981 and Super Mario Bros. in 1985. However, by the early 2000s, Nintendo was struggling as industry giants Sony and Microsoft dominated the market.

In 2006, the company took a blue ocean approach. Whereas Sony and Microsoft, with their expensive consoles, were running focus groups on gamers, Nintendo studied non-gamers. It Iooked at the gaming industry’s noncustomers and reconstructed elements across market boundaries to create the Wii – a console based on simplicity, functionality, and interactivity, with games that dramatically raised utility for these noncustomers.

Nintendo eliminated or reduced factors that were thought to be vital in the market – high-definition graphics and sound, fast chips, controllers with many buttons, and violent lifelike games, and so on. At the same time, it raised and created factors that appealed to noncustomers such as more approachable games, a focus on fun rather than computing power, and intuitive controls.

As a result of applying blue ocean strategy, the Nintendo Wii opened up a new market pulling in traditional non-gamers and outselling all Sony and Microsoft gaming products combined. It was a huge success until the unforeseen and dramatic technological disruption that came with the introduction of smartphones and tablets.

Fast forward to March 2017 and Nintendo offers up another blue ocean strategy example with the Nintendo Switch. Answering a growing demand for simple games such as the free downloadable ones on their smartphones, Nintendo created a brand-new blue ocean with the Nintendo Switch. Instead of competing with the expensive and high-end processing power of PlayStation 4 or Xbox One, the Nintendo Switch was a small device that allowed users to play games on a TV and on the go, connecting seamlessly between one device and the other.

By 2018, it had become the fastest-selling home video game system of all time in the U.S. and outsold every other console over Christmas that year. Nintendo had reconstructed market boundaries with the Switch capturing the best of high-powered game consoles and smartphone games.

Explore in-depth the blue ocean strategy examples of Nintendo Wii and Nintendo Switch.

Stitch Fix – a blue ocean example in the fashion retail industry

Stitch Fix is a blue ocean example in the fashion retail industry. The youngest female CEO to ever lead a US initial public offering, Katrina Lake created a new market space in the highly competitive fashion retail industry. Stitch Fix is a personal styling company that mails its customers boxes of stylish, carefully selected clothing. It’s as if customers had their own personal stylists. In 2019, Stitch Fix generated $1.5 billion in revenue from their ever-growing 3 million+ customers. While most retail companies are suffering, Stitch fix is soaring.

Stitch Fix combined artificial intelligence and human interaction to create a differentiated and low-cost offering that women have been going crazy for. Katrina Lake created this new market space, combining the best of technology, human creativity and ingenuity in its products.

Stitch Fix was founded by a woman and, with 86% of female employees, the company has one of the largest female workforces in the AI space, if not across almost all industries.

To learn how Stitch Fix created a blue ocean in the retail industry, read the blog “Stitch Fix: A Blue Ocean Strategy in Retail“.

HealthMedia – a blue ocean strategy example in healthcare

HealthMedia is a blue ocean strategy example of looking across strategic groups within an industry to create a blue ocean.

HealthMedia, a player in the industry with a revenue of US$6 million, was drowning in a red ocean of intense competition. At the time, the industry had two strategic groups, one offering telephonic counseling predominantly for severe medical conditions, the other offering generic, digitalized content like you find on WebMD.

HealthMedia explored why buyers traded across these strategic groups and found that despite all the factors players competed on, buyers traded up to telephonic counseling for one overriding reason – high efficacy – while they traded down to digitized content for low cost.

HealthMedia created a new market space called digital health coaching which combines the far lower cost of digitalized content with a leap in efficacy through interactive online questionnaires that digitally matched people’s self-reported challenges with a health plan that would work best for them.

Within just two years, HealthMedia had created a blue ocean so compelling that Johnson and Johnson swooped in and purchased the company for US$185 million.

The HealthMedia case study is analyzed in detail in New York Times and #1 Wall Street Journal bestseller Blue Ocean Shift.

Viagra is another example of blue ocean strategic move in the healthcare industry. Read how Viagra created a blue ocean in lifestyle drugs.

Nickel: Driving Sustainable Growth and Empowering Society

French fintech Nickel found a blue ocean in the crowded French retail banking sector by identifying noncustomers and developing a strategy to attract them.

The typical banking experience in France is notoriously tedious. You need to make an appointment and talk with a bank manager, then provide a handful of documents to open an account. It is costly to maintain an account that is linked with diverse yet mostly irrelevant financial services.

A French entrepreneur, Hugues Le Bret, saw hidden pain points that customers and noncustomers accepted as given when using banking services. So he created Nickel, a simple and convenient banking service at low cost that looked beyond current bank customers and reached low-income earners and other people excluded by legacy banks.

Founded in 2014, the company has quickly become one of the leading fintech startups in France until it was successfully sold to BNP Paribas for over 200 million euros in 2017.

While traditional banks focused on developing financial technology to make their offerings more appealing, the fintech Nickel created a blue ocean by looking at the noncustomers the other banks ignored: low-income earners and people facing financial exclusion.

If you’re interested to learn more about Nickel’s blue ocean and how it went from a startup to achieving strong profitable growth, check out this case: Driving Sustainable Growth and Empowering Society: Nickel’s Blue Ocean Beyond Disruption

Yellow Tail – a blue ocean example in the wine industry

Casella Winery’s Yellow Tail – or [yellow tail] as it’s written – is often cited as a classic example of blue ocean strategy. Let’s look at how the company created a blue ocean in the highly competitive US wine industry.

Up until 2000, the United States had the third-largest aggregate consumption of wine worldwide with an estimated $20 billion in sales. Yet, despite its size, the industry was intensely competitive.

The US wine industry in 2000 faced intense competition, mounting price pressure, increasing bargaining power on the part of retail and distribution channels, and flat demand despite overwhelming choice.

In July 2001, Australia’s Casella Winery introduced [yellow tail] into this highly competitive US market. Small and unknown, they had expected to sell 25,000 cases in their first year. In fact, they had sold nine times that amount. By the end of 2005, [yellow tail]’s cumulative sales were tracking at 25 million cases. [yellow tail] soon emerged as the overall best-selling 750ml red wine, outstripping Californian, French and Italian brands.

How did [yellow tail] become the number one imported wine and the fastest-growing brand in the history of the US and Australian wine industries?

The traditional strategy of most wineries has always been to compete on the prestige and the quality of wine at a particular price point. Prestige and quality are judged by things like the personality and characteristics of a wine, reflected in the uniqueness of the soil, the winemaker’s skills, the aging process, and so on.

Casella Wines turned this convention wisdom on its head. The Australian winery redefined the problem of the wine industry as how to make a fun and non-traditional wine that’s easy to drink. By looking at the demand side of alternatives of beer, spirits, and ready-to-drink cocktails, which captured three times as many consumer alcohol sales as wine, Casella Wines found that the mass of American adults saw wine as a turnoff. It was intimidating and pretentious, and the complexity of taste – even though it was where the industry sought to excel – created a challenge to the inexperienced palate.

With that insight, Casella was ready to challenge the industry’s strategic logic and business model. To do so it considered four key questions outlined in the blue ocean analytical tool, the Four Actions Framework.

© Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne. Blue Ocean Strategy. Blue Ocean Shift. All rights reserved.

The outcome of this analysis was [yellow tail], a wine whose strategic profile broke from the competition and created a blue ocean. Instead of offering wine as wine, Casella created a social drink accessible to everyone.

By looking at the alternatives of beer and ready-to-drink cocktails, Casella Wines created three new factors in the US wine industry – easy drinking, easy to select, and fun and adventure. It eliminated or reduced everything else.

[Yellow tail] was a completely new combination of characteristics that produced an uncomplicated wine structure that was instantly appealing to the mass of alcohol drinkers. The result was an easy-drinking wine that did not require years to develop an appreciation for.

This allowed the company to dramatically reduce or eliminate all the factors the wine industry had long competed on – tannins, complexity, and aging. With the need for aging reduced, the working capital required was also reduced. The wine industry criticized the sweet fruitiness of [yellow tail] but consumers loved the wine. Casella also made selection easy by offering only two choices of [yellow tail] – Chardonnay, the most popular white wine in the US; and red Shiraz. It also scored a home run by making wine shop employees ambassadors of [yellow tail], introducing fun and adventure into the sales process by giving the Australian outback clothing. Recommendations to consumers to buy [yellow tail] flew out of their mouths.

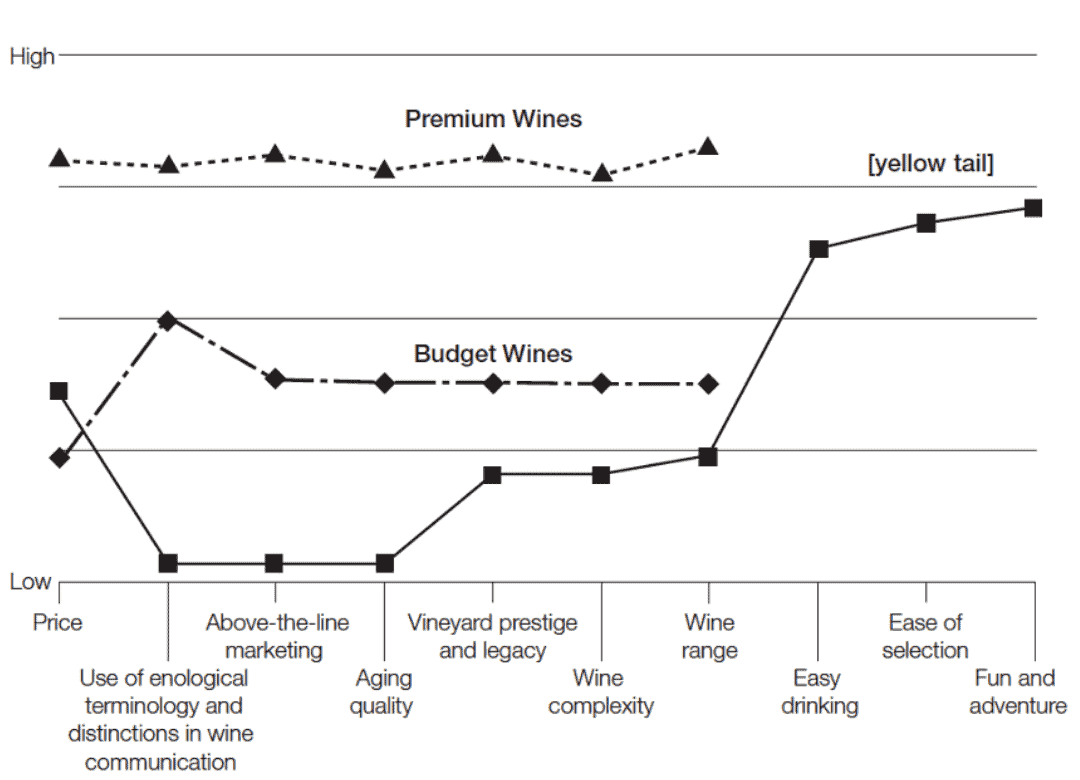

Let’s look at the Strategy Canvas of [yellow tail]. Developed by Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne, the Strategy Canvas is a diagnostic and action framework for building a compelling blue ocean strategy. It quickly captures, in one simple picture, the factors an industry competes on and invests in, the offering level of each factor that buyers receive, and the strategic profile of a company and its competitors across the key competing factors.

The Strategy Canvas of Yellow Tail

The strategy canvas of [yellow tail] shows how its strategic profile breaks from the competitors in the US wine industry. © Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne

[yellow tail] created a unique and exceptional value curve to unlock a blue ocean. As shown in the strategy canvas, [yellow tail]’s value curve has focus: the company did not diffuse its efforts across all key factors of competition. The shape of its value curve diverged from the other players’, a result of not benchmarking competitors but instead looking across alternatives. The tagline of [yellow tail]’s strategic profile was clear: a fun and simple wine to be enjoyed every day.

When expressed through a value curve, an effective blue ocean strategy has three complementary qualities: focus, divergence, and a compelling tagline.

Check out other powerful strategy canvas examples of companies like Apple or CitizenM.

To read more in detail about characteristics of good strategy read the strategy vs tactics blog where we describe it in-depth.

Cirque du Soleil – a classic example of blue ocean strategy

Arguably most well-known example of blue ocean strategy is Cirque du Soleil, a Canadian entertainment company that created uncontested market space and made the competition irrelevant. It appealed to a whole new group of customers: adults and corporate clients prepared to pay a price several times as great as traditional circuses for an unprecedented entertainment experience.

Cirque du Soleil is one of the flagship case studies in the Blue Ocean Sprint Online Course. Learn how Cirque du Soleil and others made the competition irrelevant by taking the course.

Read next:

How to Be a Blue Ocean Strategist in a Post-pandemic World

5 Compelling Strategy Canvas Examples You Can Learn From

Four Actions Framework and Eliminate-Reduce-Raise-Create Grid (Examples + Template)