Written by Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, with Mi Ji, Senior Executive Fellow at the INSEAD Blue Ocean Strategy Institute.

For the past three decades, the business mantra has been “customer first”. Yet focusing on retaining and expanding an existing customer base often results in finer segmentation and the greater tailoring of offerings to better meet customer preferences, which will likely lead companies into too-small target markets of an existing industry.

The blue ocean strategist’s mantra is “noncustomers first”. By looking to noncustomers and building on powerful commonalities in what they value, companies can reach beyond existing demand to unlock a new mass of buyers.

However, few organisations have a sound grasp of who their noncustomers are or why they remain just that – noncustomers. When we asked managers about noncustomers, some of them thought these were simply customers of their direct competitors.

Others assumed that they had no noncustomers as they were supplying all immediate downstream players in their business field. Although these managers were indeed talking about noncustomers, their mindsets continued to be confined to the narrow frame of their existing industry.

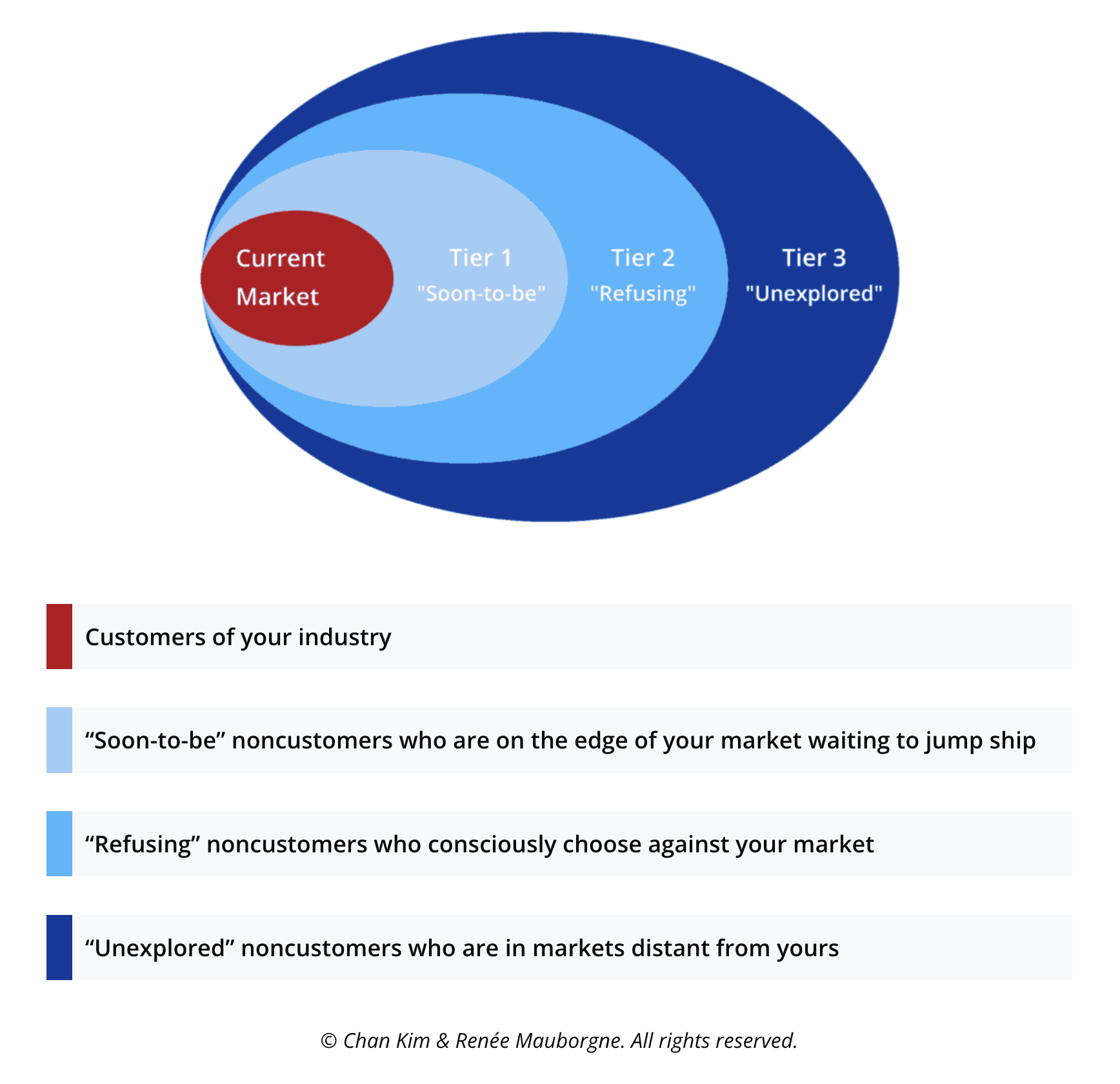

By our definition, noncustomers are buyers who don’t buy into your industry, and they normally represent a much bigger population than your existing industry’s customers.

Understanding the three tiers of noncustomers

Consider the customer relationship management (CRM) software industry. For years, CRM software vendors had focused on selling software licenses to business clients. The software was then installed, configured and customised on the premises. This required significant internal expertise and external professional support and involved a long purchase and implementation process that could last for 18 to 24 months, as well as high start-up costs and maintenance expenses.

Few organizations have a sound grasp of who their noncustomers are or why they remain just that – noncustomers.

The total cost of ownership of CRM software for 200 users over a five-year period could amount to more than US$4 million. All the vendors in the industry focused on a limited number of large business clients that traditionally used the software and had the financial resources to pay for the licenses and services. But a noncustomer analysis shows that they were ignoring the huge latent demand in the industry.

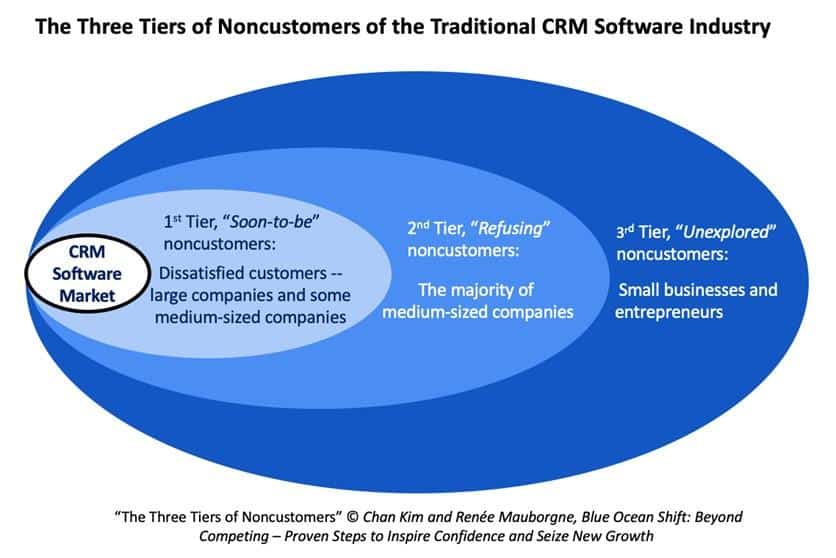

There are three tiers of noncustomers. First-tier noncustomers are all the soon-to-be noncustomers of your industry. They patronise your industry not because they want to but because they have to. They use current market offerings minimally to get by, while searching for or simply waiting for something better.

The Three Tiers of Noncustomers

In the case of the CRM software industry, these were a portion of the existing customers. This group consisted mainly of large companies and some medium-sized companies who were disgruntled about the lengthy and difficult purchase and deployment process, complex-to-use applications and low price-performance ratio. In the absence of alternative offerings, they had to put up with the existing products.

Second-tier noncustomers are refusing noncustomers. They are people or organisations that have consciously thought about using your industry’s offering but then reject it, either because another industry’s offering better meets their needs or because yours is beyond their means, in which case their needs are dealt with by another industry or ignored.

In the CRM software industry case, most medium-sized businesses found the cost of purchasing and implementing CRM solutions prohibitive despite their need to manage customer relations and sales prospects. CRM systems’ reputation for being complex, difficult to implement, having high system requirements and poor usability further drove these companies away, making them the refusing noncustomers of the industry.

Third-tier noncustomers are the furthest away from an industry’s existing customers. Commonly, these unexplored noncustomers have never been thought of as potential customers, nor targeted by any of the industry’s players, because their needs and the business opportunities associated with them have always been assumed to belong to other industries.

In the CRM software industry, these were small businesses and entrepreneurs. They normally used other means to manage their customers and sales, such as manually recording and tracking account activities and contact information using Excel spreadsheets or other database applications. Existing players in the CRM industry never thought of them as potential customers.

Case study trailer for Salesforce: Creating a Blue Ocean in the B2B Space

By looking to these noncustomers and exploring their “pain points”, Salesforce, Inc., a San Francisco-based high-tech company, created a cloud-based CRM offering. Upon subscription, customers could access and use CRM applications anywhere from any device that had an internet connection. There was no need to purchase a software license or to deploy and maintain the software on the client side.

The applications were simple and easy to use, providing only core features that met the needs of businesses of any size. The cost for accessing the CRM applications online and securely managing, sharing and using sales information was just US$65 per month per user.

Within four years, Salesforce grew from a start-up with just 10 employees and a modest investment of US$2 million into the world’s largest-hosted CRM service provider.

Salesforce’s CRM offering was not only appealing to small and medium-sized companies that had been denied access to advanced CRM solutions due to a lack of resources and infrastructure. They also proved attractive to large companies as the solution lowered their cost structure and minimised their time spent on lower-value activities, thus allowing them to concentrate their resources on activities with a greater impact on their business.

Within four years, Salesforce grew from a start-up with just 10 employees and a modest investment of US$2 million into the world’s largest-hosted CRM service provider. The CRM market has been growing at a double-digit rate, the fastest growth among all software markets.

Businesses that use cloud-based CRM solutions have swelled from 12 percent to over 87 percent in 10 years. Now, over 91 percent of organisations with more than 10 employees in their workforce use a customer relationship management system. With its blue ocean move, Salesforce tapped into the latent demand of noncustomers and created a new and fast-growing market space of on-demand CRM solutions. In doing so, it expanded the CRM industry, where it has sustained market leadership by a big margin.

Why Tata Nano failed to create a blue ocean despite its stunning debut

Similarly, the Indian automobile industry in the 2000s also presented a huge blue ocean opportunity. While the passenger car market was crowded with automakers from around the world, it was a tiny market considering India’s huge population. The two-wheeler (scooter) market was five times as big. And 90 percent of Indian families did not even own a scooter and relied on public transport for their daily mobility needs.

Despite their aspiration for better social image and status, buying a passenger car was just not an option for most Indian families given the prohibitive price; an entry-level car could cost five times as much as a scooter. Moreover, car dealerships and repair shops were only really available in big cities, making it difficult for people living in smaller cities and towns to access them. Automakers, while competing fiercely in the passenger car market, missed the potential mass market of Indian buyers seeking a decent means of personal transportation.

Here, the first-tier noncustomers were those who purchased existing passenger cars but remained dissatisfied and waited for something better. In contrast, the second-tier and third-tier noncustomers were two-wheeler buyers and the 90 percent of Indian families who did not even own a scooter, respectively.

Nano mostly reached existing car owners in big cities who were looking to buy the Tata Nano as a second car for its cheap price.

By observing what these noncustomers valued, the Indian auto manufacturer Tata Motors identified a path for blue ocean creation: The Tata Nano, unveiled in 2008, presented a safe, fuel-efficient, low-pollution and all-weather form of transport at the price of a scooter for the mass population of India.

What’s more, the company had a plan to distribute the Nano through the Tata Group’s retail networks, partner banks and post offices instead of through dealerships in big cities, thereby easily reaching two-wheeler riders in smaller cities and towns. These individuals longed for an upgrade of their socioeconomic status but were reluctant to walk into the daunting and luxurious car showrooms.

Case study trailer for Tata Nano’s Execution Failure

The Nano received rock-star greetings at its commercial launch event in 2009. As there were only 1,000 cars on display across India, most people had to place an order without having even seen, let alone test driven, the Nano. Within two weeks, the Tata Nano official website received 20 million hits. Order applications reached 200,000 – the biggest sales uptake in the history of the global automobile industry.

However, after the stunning launch event, the company – which was busy dealing with logistical and political challenges surrounding the Nano’s production plant – abandoned the plan of creating the new distribution and repair networks it had promised to noncustomers and decided to use the existing networks to save time and resources.

As a result, the Nano mostly reached existing car owners in big cities who were looking to buy the Tata Nano as a second car for its cheap price. As the Tata Nano’s reputation downgraded from the “people’s car” to the “cheapest car” to the “poor man’s car”, two-wheeler owners were turned off as the Nano was no longer a symbol of upward social mobility.

Lessons for business leaders

While the Tata Nano, initially guided by noncustomer insights, was heading towards a blue ocean, it ended up regressing into the red ocean of the existing passenger car market as a cost leader fighting over limited demand with other car makers. In contrast, it was through understanding noncustomers and delivering what they valued that Salesforce unlocked huge latent demand and created a market of previously inconceivable scale.

Do you know who your noncustomers are and what it takes to deliver what they value? Or have you been so focused on your industry’s existing customers that you cannot see beyond this narrow frame? How will you go about reframing such a mindset to create and capture expanding growth opportunities? It is time to delineate your three tiers of noncustomers and build on the powerful commonalities in what they value.

Edited by: Rachel Eva Lim

First published in INSEAD Knowledge

Check out the Case Studies

If you’re an educator interested in teaching blue ocean strategy to your students, check out these exciting case studies, which come with teaching notes to guide classroom discussion.

Blue ocean pedagogical materials, used in nearly 3,000 universities and in almost every country in the world, go beyond the standard case-based method. Our multimedia cases and interactive exercises are designed to help you build a deeper understanding of key blue ocean strategy concepts, developed by world-renowned professors Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne.

SALESFORCE.COM

Creating a Blue Ocean in the B2B Space

Author(s): KIM, W. Chan, MAUBORGNE, Renée, JI, Mi, LEE, Jee-Eun

| Case Study |

|

| Teaching Note |

|

| Lecture Slides |

|

TATA NANO

Tata Nano’s Execution Failure: How the People’s Car Failed to Reshape the Auto Industry and Create New Growth

Author(s): KIM, W. Chan, MAUBORGNE, Renée, BONG, Robert, JI, Mi

| Case Study |

|

| Teaching Note |

|

| Video |

|

| Lecture Slides |

|